It seems at times that we have forgotten the 1980s, a period of intensive activity, when Robert Combas, a graduate of the School of Fine Arts in Montpellier, made his sensational entry into the art. As early as 1977, when he was still a student, his great coup was to appropriate a world-famous icon. In 1978, he established himself with a painting on hardboard, now part of the collection of the Centre Pompidou: « Mickey n’est plus la propriété de WALT; il appartient à tout le monde BATO! » We must recall too the extraordinary interest aroused at the time by the young artist, and recognize the journey made, in such a short time, from the exhibition of the group Bernard Ceysson, « After Classicism », in 1980 (1). At the private viewing of this show, Robert Combas, who was still a student, made the acquaintance of Bruno Bischofberger, who would purchase works from him, until 1982, sometimes just on the basis of Polaroid photos, until his meeting with Jean-Michel Basquiat…

In the summer of 1981, Ben coined the term Figuration Libre: « 30% anti-culture provocation, 30% Figuration Libre, 30% art brut (art in the raw), 10% madness. The whole gives something entirely new » (2), he declared with reference to the work of Robert Combas and Hervé Di Rosa. An excess of intellectualism in art had led to the hypertrophy of the very concept of art and to its trivializing. In reaction to conceptual art, painting was making a comeback in the West. Young French artists turned away intuitively from the extremes of the avant-garde, which seemed increasingly to be worn out, and plunged, Combas among the first, into an unbridled riot of a-cultural figurations, nourished by graffiti, comic strips, television series, rock music, punk culture and B-series films.

In the years 1982-88, the « classic Combas style » asserted itself, and its place became well defined. Combas soon began 31 to do COMBAS! In 1982, the artist took part in Holly Solomon’s « Statements New York 82: Leading Contemporary Artists from France », an idea of Daniel Templon, the direction of which would be assumed by Otto Hahn: 21 French artists take part in a series of exhibitions to be mounted in sixteen New York galleries, finan-cially supported by the French Artistic Association. But, as Pierre Cabanne reported, based on an article in the New York Times, Leo Castelli flexed his muscles: in a word, the dealers went along with the scheme, but made no effort to sell the works (3)… « Does the American market need French artists? (4) » How could one hope that « a Sidney Janis or a Castelli, who have never done anything but promote American painting, should renounce all their work over the years, to convince collectors to buy French art? ». The author of the New York Times article announced unambiguously: « a reversal of roles has appeared in the rela-tions between New York and Paris (5) ». The following year, 1983, Robert Combas nevertheless had a solo show at Leo Castelli’s (6) who was the most important American dealer of the second half of the twentieth century. The dealer would repeat the exercise in 1986 (see documents pages 12-15)! In the meantime, the artist was the star attraction at the event « 5/5, Figuration Libre, France/USA », a confronta-tion between the French and the Americans, who were that day on equal terms at the ARC, at the Musée d’Art moderne of the City of Paris. Otto Hahn and Hervé Perdriolle brought together Rémy Blanchard, François Boisrond, Robert Combas, Hervé and Richard Di Rosa, who were presented along with Jean-Michel Basquiat, Crash, Keith Haring, Tseng Kwong Chi and Kenny Scharf. An historical note: how not to think of the New Realists? Two decades earlier, the 7th of June 1962, the American dealer Sidney Janis was in Paris. He wrote to Pierre Restany, the critic-theorist and founder of the New Realist movement, to request a rendezvous. The reputation of the « planetary critic » (7) had crossed the Atlantic, and Sidney Janis wanted to organize a show Nouveau Realism-Néodada for the autumn. The two men agreed on the title « The New Realism ». Pierre Restany submitted a list of artists, and wrote a preface. He had at last found an opening for his movement in the United States. He firmly believed that this would ensure the promo-tion of his artists. America in the early 1960s was everybody’s dream, and particularly the artists’. On November 5th, the critic arrived in New York. At 2pm, he visited the exhibition in the com-pany of Janis. Huge surprise, shock: the New Realists were not confronted with Rauschenberg, Johns, Stankiewiecz as he had expected, but with their little cousins who were just emerging into prominence. He discovered artists he had never heard of: George Segal, Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine, Robert Indiana. A few months later, Pop Art would be consecrated as the second 100%-American style. The French critic was forced to recognize that behind the event was the logic of an ultra-nationalistic American strategy, whose economic dominance was indisputable. The Americans had quite simply exploited the prestige of Pierre Restany to promote a new New York mainstream. The rest is history: Pop Art took off, aided by the implacable strategy of Leo Castelli in New York and his wife in Paris. The future superstars of Pop Art would play a major part in the triumph of American art. The trans-Atlantic soft power was on the march (8). It would not be so obvious for the New Realists. The history of Figuration Libre shows, twenty years later, some sombre similarities. The American artists, like Keith Haring and Basquiat, came to Paris to be consecrated and would find solid support in this country, on which to build their careers. At the same time, in the ongoing game of analogies, how not notice that after this show, Keith Haring, who had expressed a lively interest in the work of Robert Combas, would seem to have come under his influence (9)? The painter, a native of Sète, whose grandmother had the habit of putting her pink girdle on her bed every night, was soon using the shade, a flesh-coloured pink, in his paintings. « Coincidence or not » (10) the colour would be borrowed by Keith Haring several months after the show « 5/5, Figuration Libre, France/USA ». It is clear in any case that if there was influence between Americans and French, as is suggested on a panel of the exhibition « La Figuration Libre, Historique d’une aventure » the precedence of Robert Combas is in no doubt (11). And if influence there was, everything points to its having been in one direction only. We might add, as Yvon Lambert, who collaborated with the artist from 1982 to 1993 observed, that « Robert Combas is someone who is fundamentally honest, a great colourist who has never manipulated dates (12). »

Although everything seemed to start well, the American dealers, aware of the quality of Robert Combas’s works, did an abrupt about-face, sacrificing anything than might inconvenience soft power, to which they subscribed actively, erecting the glass ceiling that exists still today.

How to present Robert Combas in 2015? Choices must necessarily be made, for various reasons. The venue is certainly magnificent, but it imposes certain constraints, as does the time factor; we had to be be realistic. Naturally, we have opted for a selection within a corpus that dates from 1985, guided by instinctive preferences as well as by genuine emotional motivations.

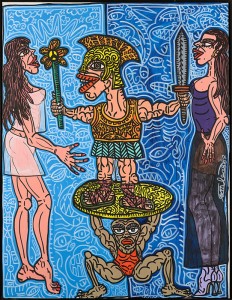

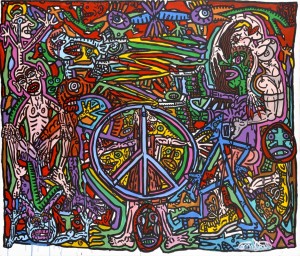

It is in any case with great humility that I begin this text. I had to ask myself the question: was it really useful to add to the impres33 sive sum of existing publications on the artist, knowing as well that since the beginning, the words he inscribes in the margins of his works invades their space-time so as to remodel yet fur-ther our perception of it? We know that from Petrarch to Roland Barthes, not to mention August Strindberg and Victor Hugo, a number of major literary personalities have devoted much of their time to the image. On the other hand, artists such as Arp or Picabia, to mention only two, have also played on both registers. Robert Combas has always bathed his paintings in words. He writes as he paints. Even more, he invites us to adopt and to invert a dialogue of the American poet, E.E. Cummings: « Does your painting not disturb your writing? On the contrary, they adore each other. » And it’s obvious: the painter slips with delight from the image to the word. Leo Castelli, who had immediately grasped the advantage to be drawn from this singular dimension, underlined its significance by reproducing, in the exhibition of 1986, the French texts referring to the canvases being pres-ented, accompanied by their English translation (13). What better homage can we render to an inveterate lover of word-play, than to observe that his name itself is a pun, expres-sing perhaps the enigma of the man: what does Robert combat, if not Robert Combas? Here in fact is an artist who takes the time to comment on each of his productions in a few lines of poetical text, resonant with rhyme and alliteration, bending and stretching grammar, often just for the sake of laughing, and who announces provocatively: « All of these texts are just talking rub-bish, but the paintings not really; well, maybe a bit! » So, even the paintings were created to make « nonsense—just a bit »? They would sometimes be augmented by nudges and winks and other image-play, in parallel with the word-play. The artist deliberately puts up smokescreens and confuses issues, for one has not truly lived who knows nothing but laughter on one hand, and the tragic mask on the other. And to create is always to scream! Designing battles from their beginning, as children often do, he persisted in exploring this theme, only to denounce the folly of all wars, such as that of 1914-18, which he depicts as fratricide in a painting of 1985 inspired by Verdun, T’auras du rata, where the combatants tear each other to pieces, unable to read the words the artist superimposes over the chaos: « My brother ». The sol-diers, whether dressed in grey or in green, are all brothers. In the spirit of the famous slogan of 1968 – Make love, not war – Combas composed a work bewitching in its ambiguity, Le partageur (1987), in which a soldier who rather resembles the artist, borne in triumph, offers with one hand his sword to a woman, and with the other a flower showing the anti-war symbol, to another woman dressed in a transparent garment. Or perhaps the two female figures who look very much alike, are just the two faces of Woman herself, whom the man wants at the same time to combat and seduce. This interior combat of the beating heart, Robert would depict it even more vividly in 1987, because at that time, she who would remain his muse and his model, came into his life. She and he appear, eyes riveted on each other, preparing to commence the Bataille intemporelle, in the magnificent canvas of 1988, in which the hand-to-hand combat of love supersedes all other wars. Two decades earlier, we had seen the huge demonstra-tions against the Vietnam War, but also the great gatherings like Woodstock, where Jimi Hendrix reinterpreted The Star-Spangled Banner in a guitar solo in which he imitated the bombardments by B-52s in the war.

Events like those often turned into gigantic happenings extolling free love, which the artist seems to recall in his own way in the painting Quand c’est la guerre, y’a meme des mythiques qui piquent (1988). But is free love always possible? Je compatis à rien (1987) claims the artist, who shows a man in workman’s overalls dropping a nude woman onto her back in front of him, while she offers him an enigmatic little grey head stuck on the end of wooden stick. The scene seems to be set in some Eden full of flowers and serpentine shapes, in which Eve offers to Adam, not some forbidden fruit, but perhaps the fruit of their love-making.

The sole haven of peace for the painter may have been the flowered garden of Ma petite Mamie (1998). An artist only ever shows enigmas. Is a canvas that does not pose questions to the spectator, really a work of art? When Saint-Georges (1991), pierces the dragon with his lance, is the noble knight symbolically making love to a monster? It certainly isn’t Les Bandits de l’enfer joli (1987) who could pass for monsters; these strange spindly beings are nothing but a bunch of loonies disguised as gangsters.

The vaguely gypsy or Circassian quartet, in the painting Les Musiciens (1989), perform a diabolical music, which makes even the floor tiles dance, under the brush of a « rock painter », the artist’s own expression. He is not content to create only images, but rhythms too. At the beginning of his career with the group Les Démodés (14) and today with Lucas Manicione with whom he joins in real performances, in which music is the foundation, Robert Combas enters into a sort of trance, so to speak, miraculously inventing a harmony extracted from a sound-raid. It is certain, in any case, that the spectator does not leave unaffected this confrontation imposed upon him, visually and musically, by 35 the artist. I had the privilege twice, to experience the event on screen in his studio. It left a significant impression on me, of a striking gestural language and a dazzling spontaneity. It must be emphasized that, behind this festival of attitudes, of pictorial acts, stands a dense, powerful body of work, utterly coherent and impassioned.

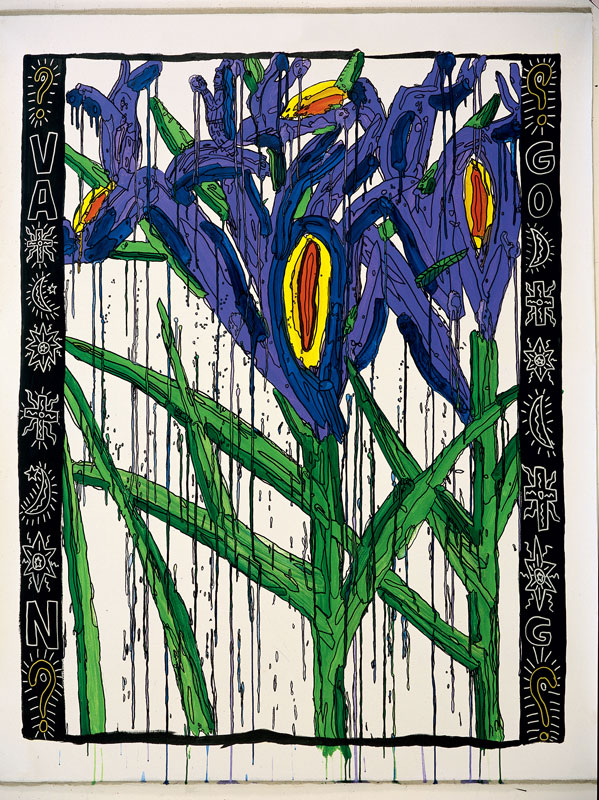

That is perhaps what a « rock painting » is, to use the artist’s own expression. Not the one deposited on a guitar, unmistakeably female, Guitare Combas (2003), but rather the one that mixes electric sounds with the roaring of a motorcyclist, a powerful image like Le Motard et les deux guitares (2007). Because the work is not created by the artist to incite mere open-mouthed ad-miration; it is rather a challenge to be taken up with one’s vision, or a battle to undergo. But are not the most impressive sounds those of colours when they weep? The streaks of paint are thin, when Robert Combas amuses himself by showing Les Iris géants (2008), imitating the work of VAN GOGH in the two lateral bands, which are otherwise filled with the symbols of the three religions that believe in Eden. But when La peau des fleurs (1999) does not fall apart in shreds, it is because it is liquefied like the human beings of Hiro-shima, immortalized as they died, to transform itself into fluids, leaving a photographic impression on the walls rendered photo-sensitive by the atomic flash. The painter offers here one of his most striking works, in any case one of his least wilfully nonsen-sical: three heads stuck on bodies, each one reduced to a mere backbone, spines with no more than short leaves suggestive of stumps of arms. The heads are already so bare of flesh that they are nothing more than skulls crowned with coloured petals in the place of hair; between a blue masculine flower and feminine rose, a blond flower stands perhaps for childhood between two parental figures. It remains to be known what family trio this is, and what cataclysmic explosion could have blasted this flower family.

The series of canvases, of which Petit chien console petit saint, L’Icône ostensoir, and La peau des fleurs are part, use the same technique of streaks. Do they perhaps offer an answer to the mystery? Nearly all framed by black bands on two or all four sides, these works with the appearance of funeral notices, may also represent windows veiled with transparent, striped tulle, or curtains made of strings of pearls. And behind each of these openings that allow a glimpse of the external world, a human figure can be discerned. Masculine figures appear rarely, but the few that do are in works of an exceptional quality, such as Pauvre Martin (1992), who is wearing himself out digging a field dried by a merciless sun, or Monsieur Henri dégoulinant de sensibilité (1990) who, on the contrary poses before the setting sun which magnifies him; on the other hand, a radiant sun is given a position of dominance in L’Icône ostensoir (1990). Another figure of female sovereignty is the one who sprawls on a hill of blue-coloured heads collected as trophies, like the Kali, the Hindu deity adorned with severed heads, while Le grand soleil échaudé (2008) of the piece’s title does not even attempt to slip behind the queen in order to make her appear more brilliant. Booted and corseted, this female version of Tamerlan the grim builder of pyramids of heads, does not divert her glance. In the same vein is the woman-robot with nerves of steel, Ho Marylin ordinateur (2000). But are the figures of women always so powerful, in the artists’ eyes? Contrary to the icy Marylin, there suddenly emerges from a small house in the forest, a timid and touching Marilune, her face wrapped in a scarf knotted under her chin, and wearing, almost laughably, a paper crown. A day of epiphany perhaps, the one moment when the fairies, thanks to the magical virtues of a bean, can make a queen of a little peasant girl, Marielunelarme (2000)? With her sweet little face reddened by the cold, softened by a tear and wearing a songbird drawn on her forehead, is it possible that this little shepherdess has caught the eye of a prince of art, just long enough to paint her? Or is it yet another facet of Woman, glimpsed in reverie, so different from those images of strong, free femininity, desirable and formidable at the same time?

But there are those who dream of being attached, bound, says Robert Combas in the commentary on a painting where the famous Liberté, title of poem by Paul Eluard, is illustrated by a gloomy place where prisoners are chained to one another; this is the work Je crie ton nom Liberté, j’écris mon ton saleté, 2009. While in Les corps étaient d’acier (2011), a person of ambiguous sexual identity, though nude, hides its face to avoid the vengeful beak of bird of prey that fixes it with its glare, illustrating the « spirit of paradise », this mysterious phrase appears, written in pink and blue letters. Sated, though not with sexuality, the anatomies seem to have the strength of metal, but it can ultimately melt, whereas the spirit has only the lightness of a bird, but a bird of paradise.

Few figurative painters, issued from the harsh school of expressionism, have come to the fore in the last half-century. Robert Combas, with his art of excess and outrageousness, while developing an exciting and powerful body of work, is one of those. Without doubt, his art is not opting out, an escape, but rather an act of revolt, of experience feverishly tested, that reveals the interdependence of a life and a work.

In this exhibition at the museum of Touquet-Paris-Plage, a last 37 group of paintings using mixed techniques, like Homme frisé barbu, or Matrone à enluminures or Explosage de mini energies, belong to the field of appropriation of antique or classical works of art, the sources of which would seem to be inexhaustible. The play of images here assumes all of its meaning. And here Robert Combas the Magnificent lets himself go joyfully, titillating the observer, challenging him to recognize the originals, the works he has hijacked. And he accompanies this game of hide-and-seek with a new avalanche of words, as if to cover up with a defensive laughter his earlier works which perhaps allowed too clear a view into intimate mysteries, the secret pathways leading into the interior. Putting a beard on the chin of a Roman emperor, or a bad-tempered expression on the face of Renaissance Madonna, showing his culture while pretending to mock it, is also a means of making his painting apparently more impersonal, like the joyful iconoclastic propensity of a child to colour over statues or posters with crayons so as to take possession of them. The pain-tings of this series may also be seen as obituaries of a classical culture too beautiful to be true. But Art is always a long road, on which, incessantly, obstinately, the creators advance. A road on which inch by inch, indefatigably, Robert combats…

Henry Périer

Footnotes:

1) Exhibition « Après le classicisme », Museum of Art and Industry, Saint-Étienne, France 21 November 1980 – 10 January 1981.

2) Jim Palette,remarks recorded on September 29, 1981, for the newspaper Libération.

3) Pierre Cabanne, Le matin de Paris, 13 February 1982.

4) Geneviève Breerette, Le Monde, Artistes français à New York / L’invasion ? Sunday 14 – Monday 15 February 1982.

5) The New York Times, 16 galleries show New art from France, February 12, 1982.

6) « On commence par le début, on finit par la fin », exhibition catalogue, Museum of contem-porary art of Lyon, France, 24 February – 15 July 2012, page 399.

7) Michel Ragon, Foreword of Les nouveaux réalistes by Pierre Restany, Editions Planète, 1968, page 10.

8) Henry Périer, Pierre Restany, Le prophète de l’art, Editions du cercle d’art Paris, 2013, pages 186-187.

9) Interview with Hervé Perdriolle, curator of the exhibition at the ARC at Musée d’Art moderne of the city of Paris, 15 June 2015.

10) Note in catalogue de l’exposition, Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon, page 399.

11) Exhibition « La Figuration Libre, Historique d’une aventure », Musée Paul Valéry, Sète, France, 3 July – 15 November 2015.

12) Interview with Yvon Lambert, 16 July 2015.

13) Pages 14 and 15 of this catalogue.

14) The group Les Démodés was formed in 1978, with Ketty Brindel and Richard Di Rosa.

![[EN] Combas.com](https://www.combas.com/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/01/logo-reseau.png)