“Said welcome to the spirit of 1956/ Patient in the bushes next to ’57/ The highway is your girlfriend as you go by quick/ Suburban trees, suburban speed/And it smells like heaven (thunder)/ And I say roadrunner once/Roadrunner twice /I’m in love with rock’n’roll and I’ll be out all night/ Roadrunner That’s right

“Well now Roadrunner, roadrunner/ Going faster miles an hour/ Gonna drive to the Stop ‘n’ Shop/With the radio on at night And me in love with modern moonlight/ Me in love with modern rock’n’roll/ Modern girls and modern rock’n’roll Don’t feel so alone, got the radio on Like the roadrunner OK, now you sing Modern Lovers

“(Radio On!) I got the AM (Radio On!)/Got the car, got the AM (Radio On!)/Got the AM sound (Radio On!), got the (Radio On!)/Got the rockin’ modern neon sound (Radio On!)/I got the car from Massachusetts, got the (Radio On!)/I got the power of Massachusetts when it’s late at night (Radio On!)/I got the modern sounds of modern Massachusetts (Radio On!)/I’ve got the world, got the turnpike (Radio On!), got the I’ve got the, got the power of the AM got the (Radio On!), late at night/rock’n’roll late at night. The factories and the auto signs got the power of modern sounds (Radio on!) Alright”

“Roadrunner” Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers1

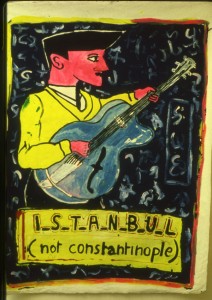

The works of Robert Combas are not just influenced by the lyrics, gestures and vocal textures of Patti Smith, the Ramones and Jonathan Richman (and many more), but also by the different ways in which he perceives these rock stars – in other words, whether they are heard live, recorded, over the radio or seen in a blister pack. Not only does he listen to music, but he also collects and plays it.

“La Figuration Libre, means relaxing – having fun, as they say in English. That’s a term from pop music.”2

“Originally, I wanted to call my painting ‘fun painting.’ That was a problem for me because it’s an English word. I didn’t have a name for my painting because I was the only person doing it, but at the Beaux-Arts I called it ‘fun painting, amusing, light-hearted painting.’” I still call it ‘amusing and relaxed’ painting, which means the same thing.”3

As he explains here, Combas broke Figuration Libre down into different com -ponents, revealing its nature and its relation to the visual arts, but also to music. In 1978 the artist formed a group, Les Démodés, with Ketty and Richard Di Rosa.

Today, he has been working for going on two years with fellow musician, artist and friend Lucas Mancione and Pierre Reixach. In one of their videos, Combas sings with a mask on his face. He plays the guitar, usually rather simple melodies. In the 1950s, says Lou Reed, “there was the four chord school, C, Am, F, G. If you knew these you could play 400 songs and the top 20 – ‘Blanche,’ ‘Why Don’t You Write Me,’ ‘In the Still of the Night.’ Elvis was three chords, E, A, B.”4

Today, he has been working for going on two years with fellow musician, artist and friend Lucas Mancione and Pierre Reixach. In one of their videos, Combas sings with a mask on his face. He plays the guitar, usually rather simple melodies. In the 1950s, says Lou Reed, “there was the four chord school, C, Am, F, G. If you knew these you could play 400 songs and the top 20 – ‘Blanche,’ ‘Why Don’t You Write Me,’ ‘In the Still of the Night.’ Elvis was three chords, E, A, B.”4

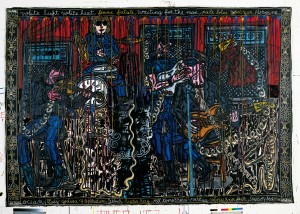

Combas says: “I work in releases of paint, a kind of abstract expressionism. The figurative is the fun side.”5 His aesthetic was formed in the age of pop music, that is to say, music that is mass distributed in the form of records. Right from the start, even before Bill Haley and His Comets6 came along, the contents of pop music were determined by its means of distribution. Popular culture needs to repeat simple structures and actions, not only for commercial reasons but also so that these actions can be duplicated and imitated. Apart from his sculptures and prints, Combas’s works are not produced in series, but there is no denying that, like pop music, they are “inspired” and of the moment. The elements of his art vary with the influence of the rock icons of the time, but also with that of comic book characters, illustrations for children’s books, personal events and historical happenings: his work is truly tied to pop culture images, and more generally to the Zeitgeist.

Just as Susan Sontag sees a connection between Patti Smith and Nietzsche7 (“In the way she talks, the way she comes on, what she’s trying to do, the kind of person she is. That’s part of where we are culturally.”8), it is possible to see Combas’ work as in part a carryover from the Romanticism of the 18th and 19th centuries. There is not, then, some radical break between history and Combas’ work. “Figuration Libre is when I do a cartoon with a funny hero and then next morning I drop it all to make a big canvas about the Battle of Waterloo.”9

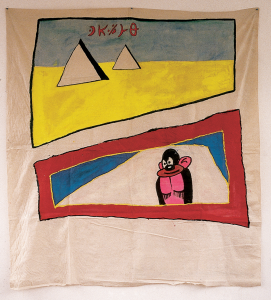

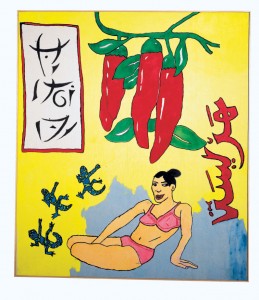

At the same time, Combas’ work resonates with the writings of Marshall McLuhan, with whom he shares a desire to achieve a universal language. “However, I think that the message of my paintings is totally abstract: it’s a mixture of images, colours, false Asian, Arab and South American writing, painting that is an attempt at a universal language.”10 Images of death and sex echo the violence done to the innocent in real life. But real life cannot be effectively approached in a realist form, only by means of a deliberate “formal imperfection”. (“Figuration Libre, it’s putting colour on a badly done drawing, it’s hiding the imperfections of a painting with black and in that way bringing out the colours by surrounding all the forms.”11) It goes without saying that this imperfection is not the result of a technical weakness. On the contrary, it is a choice, a conscious answer to the thorny problem of the visual arts in the postintermedia era from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s, a time that witnessed the emergence of various Neo-Expressionist forms around the world: Bad Painting in 1978, the Transavanguardia in 1979, the Neuen Wilden in 1980 and Figuration Libre in 1981 (but then, Combas began in 1977).

At the same time, Combas’ work resonates with the writings of Marshall McLuhan, with whom he shares a desire to achieve a universal language. “However, I think that the message of my paintings is totally abstract: it’s a mixture of images, colours, false Asian, Arab and South American writing, painting that is an attempt at a universal language.”10 Images of death and sex echo the violence done to the innocent in real life. But real life cannot be effectively approached in a realist form, only by means of a deliberate “formal imperfection”. (“Figuration Libre, it’s putting colour on a badly done drawing, it’s hiding the imperfections of a painting with black and in that way bringing out the colours by surrounding all the forms.”11) It goes without saying that this imperfection is not the result of a technical weakness. On the contrary, it is a choice, a conscious answer to the thorny problem of the visual arts in the postintermedia era from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s, a time that witnessed the emergence of various Neo-Expressionist forms around the world: Bad Painting in 1978, the Transavanguardia in 1979, the Neuen Wilden in 1980 and Figuration Libre in 1981 (but then, Combas began in 1977).

“Distortions in the use of the figure are related to the element of fantasy, of the difference between the way the mind imagines things and the way they are actually seen,” writes Marcia Tucker in the catalogue to the 1978 exhibition Bad Painting at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, which featured the works of artists who, at the time, were virtual unknowns in New York: William Copley, Neil Jenney, William Wegman, Shari Urquhart and Robert Chambless Hendon. In the works shown in this exhibition, “the psychological, formal, emotional, and intellectual imbalance created is part of the function of all advanced art”12 and veers towards parody because “convention is the opiate of the masses.”13 While Combas’ art has a number of things in common with these practices, it is in fact a mixture of the sophisticated (high) and the popular (low): “Dadaism Art Brut, Art Nègre, the art of naive public painters in Haiti, Africa, South America, Jamaica, naive art, Arte Povera, rock’n’roll, rock culture, the art of misfits (Down’s syndrome), Picasso, Expressionism, Impressionism, comix: mix it all up and you get Combas, figurative because I live in a world of realities.”14

Combas’ work and the culture that influences it are too immediate, too spontaneous and too “honest” to be about parody, nudges and winks and posturing. That was how rock’n’roll, especially in the “No Future”15 movement, came into the world. It was an élan and an incitement. Lou Reed, one of the founder members of the Velvet Underground, sums up the situation thus: “We are all made to love the music. And the word love was used and used and used in all music. Overused, again and again, because that’s where it was at.”16

Combas’ work and the culture that influences it are too immediate, too spontaneous and too “honest” to be about parody, nudges and winks and posturing. That was how rock’n’roll, especially in the “No Future”15 movement, came into the world. It was an élan and an incitement. Lou Reed, one of the founder members of the Velvet Underground, sums up the situation thus: “We are all made to love the music. And the word love was used and used and used in all music. Overused, again and again, because that’s where it was at.”16

Apart from a few bluesmen who came before, Reed was part of the first generation of rockers to be fully aware of this essential and universal human dimension which goes beyond the commercial aspect of pop music. They were the first “modern” rock musicians. As Reed says, “Real people are coming up fast. Real because they’re here now, alive, while the others are dead, and because they wouldn’t give Robert Lowell a poetry prize either.”17

Combas puts it like this: “It’s the feeling I look for. The feeling is the rhythm, the wild drummer in the jungle and voodoo dances. It’s the Rolling Stones copying old pieces by blacks, bluesmen, and creating a new music without even meaning to. It’s a bit like that for me with painting, getting the rhythm (feeling) of writing and painting from advertising, from China, the Arabs and the Mediterranean. My painting is rock.”18

Hiroshi Egaitsu

- Robert Combas’s favorite proto-punk rock band.

- See the artist’s website: www.combas.com

- www.combas.com

- Johan Kugleberg, ed. The Velvet Underground New York Art, New York: Rizzoli, 2009, p.104.

- www.combas.com

- Bill Haley and His Comets are recognized today as one of the most important rock’n’roll groups of the 1950s.

- Leland Poague (ed.), Conversations with Susan Sontag (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. 1995) p.115.

- Ibid., p.115.

- www.combas.com

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Bad” Painting, exhibition catalogue New York, New Museum of Contemporary Art, 1978, p.19.

- Ibid.

- www.combas.com

- This slogan was in the chorus of the Sex Pistols single “God Save The Queen,” 1977.

- Johan Kugleberg (ed.), The Velvet Underground, op. cit., p.104.

- Ibid., p. 105. Robert Lowell (1917–1977) is widely considered the most important American poet of the postwar decades.

- www.combas.com

![[EN] Combas.com](https://www.combas.com/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/01/logo-reseau.png)