Gaudy Redskins had taken them for targets, Nailing them naked to coloured stakes.

Arthur Rimbaud, The Drunken Boat

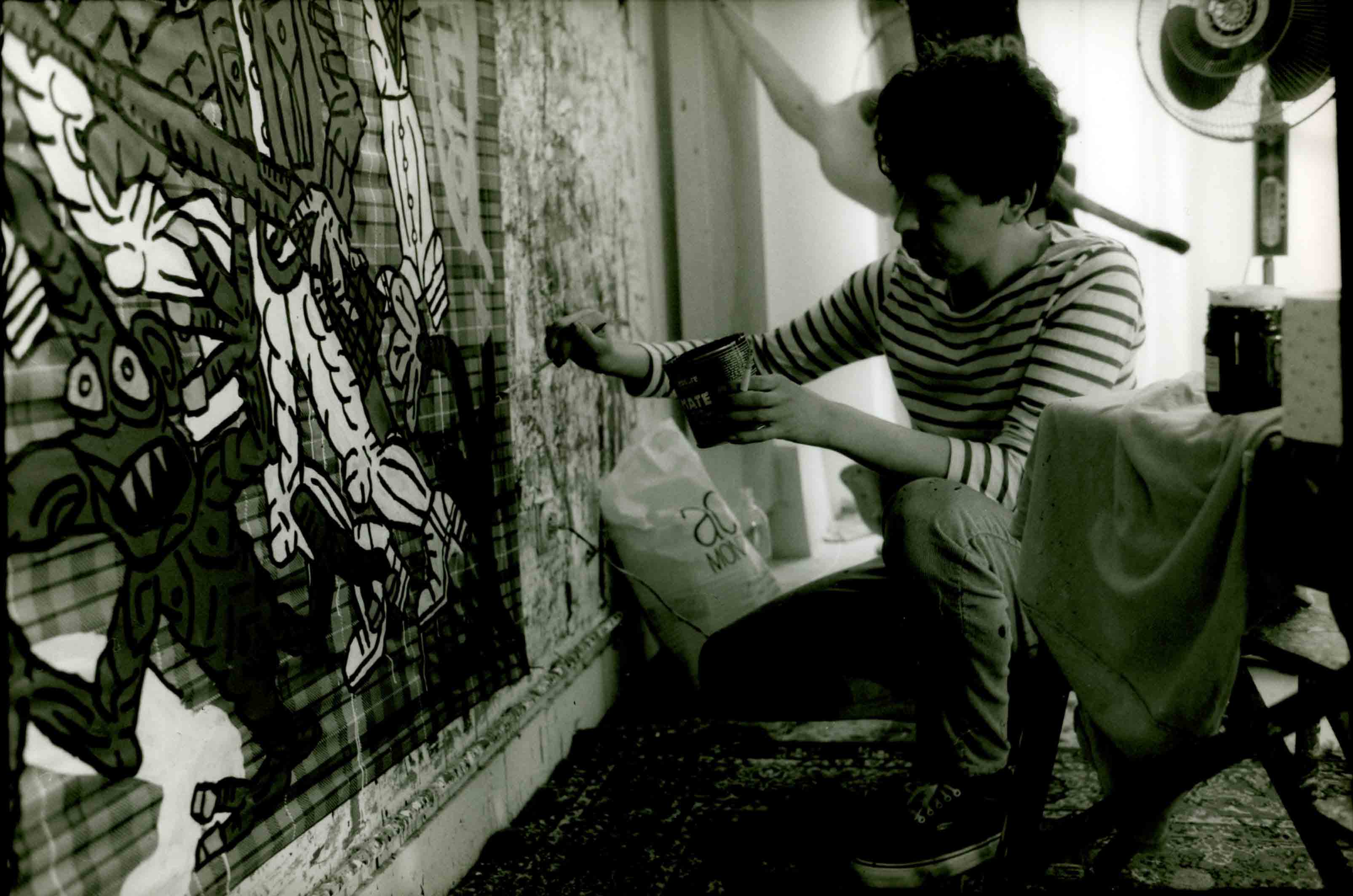

Robert Combas is a painter. He is a painter in all senses of the word, a painter who covers up everything on which he is able to put his hands, be they sheets, panels, objects, musical instruments, furniture, etc., and he does so with greed and voluptuousness, with generosity and humour. He boasts a reputation among the best-known and most-collected artists in France today, and his warm personality is only one of his many features. His generosity is reflected through his firm personal and public stands, his rambling yet subtle speech, his diversified and invading work, his ordinary and heroic themes, his energetic and limitless brushstroke, his radiant and lush colours…

Born in an extremely simple environment, but open to art and keen to learn about it, Robert Combas spent his youth in Sète, a Mediterranean seaport located in Southern France. He had an innate gift for drawing and his parents encourage him in that field. “I used to draw all the time, almost instinctively, automatically. I never stopped, and when I was 6 or 7, my parents told me that I should register at the School of Fine Arts … Hence, I stayed there until I was 23… I was not really happy to be there, but if my parents had not pushed me, I would probably not have done anything by myself.”

As all teenagers of his generation, he enjoyed comic strips and rock music.

“I always liked illustrations, comic strips, such as Vaillant, Pif le chien, Pilote, Tintin or even Francs Jeux. The latter was a wonderful periodical with César, the cartoonist of Arthur le fantôme (Arthur the Ghost). In the middle of the issue, he would use the centrefold as a fresco or a battle and fill it jestingly with tons of characters in line with Dubout’s style. The newspapers my father read also had a huge influence on me and I made cartoons inspired by the Canard enchaîné. Rock music was also a favourite of mine and I used to do some with my friends. When I was very young, I found out that its rhythm suited me very well.”

He studied at Montpellier’s School of Fine Arts, a typical French provincial school boasting a post-1968 mentality, with teachers, either too academic or under the influence of the Supports/Surfaces Group, conceptualists and minimalists.

“That was in 1977, I was in contact with young and switched-on people who had a certain degree of creativity. The times were slightly punk, and many members of the younger generation were comic-strip fans. At the School of Fine Arts, everybody had deserted except a bunch of old-fashioned hippies more or less influenced by Supports/Surfaces or their teachers. I had chosen painting, and towards the end of the first year, I told myself that I had to do something new. I looked at what I was doing – battles – and I said that I should do as I used to when I was just a kid: a battle on a larger scale and with paint in total opposition to my doodles with a pen. I sat at a table and did three paintings.

“Everything started there, with a return back to my childhood days.

“I always did a lot of battles, because when I was little, I would scribble graffiti on my exercise books. My first canvasses were called Bataille de cow-boys contre Indiens (Cowboys Fighting Indians), Japonais contre Américains (Japanese Versus Americans), Bataille navale (Naval Battle), etc.

“I had always wanted to do something entirely new, I had always felt the need to be different from others, I truly consider myself to be a dandy.”

His works were at counter-current with conventional – but actually quite comfortable – academic productions and were noticed the same year he graduated.

“Consequently I obtained my degree in painting at Saint-Étienne in front of a panel that included Bernard Ceysson, Director of the Saint-Étienne Museum. He liked my work a great deal and suggested that I participate in an exhibition called Après le Classicisme (After Classicism) at the Museum. When I asked him why he did, he replied that there were not enough people doing my type of work; he also added that my paintings resembled very much those of the Italian Trans-Avant-Garde and the German New Fauves, and yet, stood apart from them. I took part in the exhibition where I met Bruno Bischofberger, Daniel Templon and other people who not only studied my canvasses with interest, but also bought some.”

Success was at hand and exhibitions started to follow each other very rapidly, first in 1980 at the Saint-Étienne Museum of Art and Industry, with Après le Classicisme (After Classicism); then Finir en beauté (Ending Up in Beauty), in 1981, at the residence of art critic Bernard Lamarche-Vadel, who gathered the four painters of Figuration libre (Free Figuration) for the first time: Rémi Blanchard, François Boisrond, Robert Combas and Hervé Di Rosa [attending the exhibition were: Catherine Violet, Jean-Charles Blais and Jean-Michel Alberola], as well as Deux Sétois à Nice (Two People from Sète in Nice), an exhibit organised by Ben Vautier who coined the term Figuration libre to qualify their work. Then followed Ateliers 81-82 (Workshops 81-82) at the Paris Museum of Modern Art where Robert Combas achieved great success with his group, “Les Démodés”.

His works are shown in the most famous galleries: in France, at Yvon Lambert’s as early as 1982, and abroad, in New York, as early as 1983, at Léo Castelli’s, who considers him to be a very good painter, even better than Haring. Finally, in 1985, the first retrospective was organised by three particularly active and courageous museums: the Museum of the Sainte-Croix Abbey (Les Sables d’Olonne, France), the Gemeente Museum (Helmond, Netherlands) and the Museum of Art and Industry (Saint-Étienne, France).

Working relatively isolated, even secluded, from the world of crazes and society life, Combas has protected himself. His work is different mostly by its integrity. His attitude could be qualified as a democratic, social and provincial revenge. It is diametrically opposed to that of Warhol, which revolves around the idea of communication, social success, fad and widespread diffusion.

The work of Robert Combas, nurtured by quotations, Avant-Garde thoughts (Cobra, Raw Art, Dada, Pop Art, to quote them haphazardly as he absorbs them), underground culture for its mockery and anti-heroes (Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Fritz the Cat by Robert Crumb), caricature for its irony and disrespect (Reiser; Cavanna and Professor Choron in Hara Kiri; Gotlib in l’Écho des savanes), traditional culture (Mediaeval phylacteries, Romanesque wall paintings, gothic stained windows, Persian miniatures) is characterised by its rejection of any allegiance and by the constant attraction for improvisation. It is the social expression of an urban tribal conscience fusing a parody of kitsch art, with perverted avant-garde principles to which he remains indifferent. It reflects the anti-culture of the broadest public.

His work stands out by the colour and the black contour of his figures, effervescence and vitality, joyous and happy frenzy, irony and parody, the abolition of all hierarchy between content and form, the absence of volume and perspective, entanglement and compartmentalisation.

“For me, a painting may be influenced by African naïve publicists, by the illustration of primary-school books, mixed with Picasso or Miró, or else by comic-strip drawings, plus Arabic calligraphy, plus a raw painting very much in Dubuffet’s or Cobra’s style. Free Figuration is a painting that does not disavow its primitive instincts; it expresses a constant search for culture.

“Dadaism, Raw Art, Negro Art, that of the naïve publicist painters of Haiti, Africa, South America, Jamaica, Naïve Art, Poor Art, Rock ‘n’ Roll, Rock Culture, Exceptional and Misfit Art, Picasso, Expressionism, Impressionism, comic strips. Mix everything well together and you obtain Combas as your end result: I am a representational painter, because I live in a world of realities. On the other hand, I find that the message of my paintings is abstract in nature. It is a mixture of images, colours, false Asian, Arabic or South-American calligraphy, a form of painting aiming to be universal.”

“Sometimes, I simply throw paint, a form of abstract expressionism. Figurative painting is amusing and represents my down-to-earth side of things; initially, it was a mocking reaction against intellectual paintings of the art world in the mid-70s. Since I was born in a working-class environment, I was living in two different worlds. There are still messages in my paintings: at first, it constitutes a form of energy, because I want to paint what I like. In comic strips, the artist is hindered by the characters, whereas in that sort of painting, I am entirely free even with regard to format.

“My painting is very free and remains for me a means to remain honest.”

The common character of the work is violence and the purity of colour, features that both refer immediately to fauvism. The term fauve characterises first a very precise period in time and a group of well-identified artists, but it is also used to qualify artists or works that refer to either of them, such as the words archaic, classical or baroque.

The work is also noticeable by the constancy of certain topics, oscillating between the violence of either the simulated wars of children or the real wars of adults, and love, the love he feels for others in general and the love he feels for his fiancées in particular, between turmoil, meditation and fury. It is also noticeable through the style, which guarantees consistency, while affirming certain periods generating successively one another in sudden developments and new inspirations, etc.

The early 80s with their violence and their pure colours could be qualified as “fauve years”, the symbol of youth and modernity, whereas the last years could be described as “the most sex-oriented years”, especially with battles in 1988, which are very assertive of the Combas style. Works with colour are paramount, because colour fills the entire space of the canvas. A black contour line surrounds it with an obsession that reinforces its appeal. “Small heads perk up everywhere, along with feet and genital organs. Words surge and supersaturate the meaning. Senses explode. Writing yields back speech to images in both the symbolical and actual spaces of the imagination in the process of coming alive.” The saturated space refers to Persian miniatures of the xvth century in which appear faces or animals in rocks, trees or clothes.

Combas moves from peaceful love to war, then from poetry to music, and deals with all periods of art history and all subjects.

In early 1990, he visited churches and cathedrals, several cultural cities (especially Venice), and scrutinised sculptures, stained-glass windows and icons… He opened up to literature, History and esotericism. He developed a special craze for the Middle Ages. His curiosity influenced his work, and he qualifies himself as “a spiritual period at the first degree”.

The background of the canvas is black as a “dark night”. Runs representing falling rain from heaven as flames of a new Holy Spirit, cover characters in part. The works of that period were shown in 1989 in San Francisco and in Albi, France, in 1990. A new series inspired by the Bible was also exhibited in Paris.

Such obvious need for spirituality is reflected in the selection of large formats, up to 5 m, the size of a chapel, which evoke irresistibly as early as the late 80s the mural paintings of the Middle Ages or of the Baroque Period in the xviith century. The spiritual need grows in the early 90s through various themes referring to Oriental spiritual movements, such as Buddhism or the Christian tradition, or bathing in an atmosphere of Mediaeval legends. Works inspired by Mediaeval folklore are flooded with the same Christian spirituality, since both are closely related. Should they be seen as self-portraits associating memories of childhood readings, a far-remote catechism and an obvious aspiration to something much higher?

He remains faithful to the topics of battles, with explosions of colours, and love for women with both gentleness and tenderness […]. That gentleness found in love stories transforms itself into spiritual interrogations.

At London’s County Hall Gallery, in January 2005, Charles Saatchi set up three exhibitions on the “triumph” of a genre that part of the art world deemed dead and superseded by video and environment art: painting. As Philippe Dagen emphasised rightly so: “Painting does not look back, but continues […]. Charles Saatchi’s position […], whether as a visionary collector or a wise speculator is actually quite less innovative than it seems. In 2002, the Pompidou Centre in Paris organised an exhibition called Cher Peintre (Dear Painter) based on an identical idea, but with fewer means […].

“The real question is not about creation, but its critical reception in various locations and at different times. In New York and Berlin, painting never ceased to be on display in galleries and museums. […] In Paris and London, the situation is different. In France, cultural institutions support a modernistic dogmatism proclaiming that painting is dead, thus provoking the opposition of faithful devotees to the past in the name of ‘fine work’ and tradition. Fortunately, such sterile situation now seems to be changing.”

For Bernard Blistène: “The time for a new appraisal of the 80s is near: we shall see the complexity of what occurred, the conceptual part of the first works by Garouste and Gasiorowski or the significance of performance in the so-called ‘New Fauves’. That interpretation will be promoted by the current situation as artists keep peering at Morley, Kippenberger or Basquiat.”

Many names could be added. As for myself, I would be most happy to include Robert Combas to that list. Presenting his works today, granting them their place is not only legitimate, but salvaging altogether. They express beauty, fantasy and freedom.

![[EN] Combas.com](https://www.combas.com/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/01/logo-reseau.png)