Robert Combas’ record collection is almost as fascinating as his studio. It occupies a room all of its own, a cross between a musical Ali Baba’s cave and a chaotic dump of discs, crammed onto shelves or spread in piles of albums and singles from every period. The painter says he sometimes likes to lock himself away and draw there, in this “almighty mess that is essential to [his] art.”

This jungle of tens of thousands of records in which masterpieces sit beside obscurities and oddities is the product of over forty years of obsession with the intensities and underground realities of rock, with its sublimities and its impurities. This electrical profusion has shaped and continues to move this man who claims that “my painting is rock”—so much so that he has started playing the music again. But then again he never really stopped being a musician.

Among the many sketches and bits of graffiti with which the young boy in Sète plastered his schoolbooks, some were of rock groups and other guitar-toting, shock-haired heroes. The young teenager realised that the music he thrilled to was not French chanson but English and American rock that throbbed with excitement and modernity. There was, in particular, John Lennon, the most subversive of the Fab Four, whose single Instant Karma (1970) hit him like a revelation.

Sometimes what blew his mind was child-like and candid, at others, fraught with rebellious violence and sexuality. Combas was fascinated by the way sound makers like Phil Spector and Brian Wilson created intricate pocket symphonies to celebrate teenage emotions. His admiration for the Pygmalion behind The Ronettes and The Crystals, the inventor of the famous Wall of Sound, and for the maniacal songwriter of the Beach Boys, turned him into a compulsive collector of their work, even when performed by the most unlikely disciples.

What excited him was surely the way they managed to illuminate the modesty of popular music with amazing innovations and sounds.

Post-Woodstock rock also appealed to him with its Dionysian power and risky excesses. The young Combas loved to let it all hang out in these sessions that were like initiation rites. He quivered at the distortions of the early Deep Purple, rushed to catch concerts by The Who and by sound revolutionaries MC5. He loved The Stones, whose music blared endlessly from the jukeboxes around town. He also discovered more out-of-the-way treasures, the stylish lords of garage rock. Half-way between the elegance of The Beatles and the cocksure arrogance of The Stones, he fell in love forever with The Flamin’ Groovies, the “beautiful losers” of San Francisco led by singer Roy Loney.

Sète in the 1970s was a place where you could find a surprisingly high proportion of bands and figures steeped in these illuminations of rock. Greasers in black leather, weed-smoking dandies in fur coats with red hair and kohl round their eyes. The young Arabs posed as Black soul and funk heroes. The future painter was crazy about Black music. The primitive power of the blues of Sonny Terry and the tribal riffs of Bo Diddley were like musical art brut to his ears.

It is surely no coincidence that Combas painted his first canvases and created his first group in the second half of the 1970s, at the time of the punk explosion. This was the most liberating, the most uninhibited outburst of energy rock had everseen. These Mohican-heads who declared the end of the star system and the reign of do-it-yourself made playing music suddenly seem accessible again, and showed the way for painting.

One pioneer of the new genre made a particularly strong impression on our student from the Beaux-Arts. This was Jonathan Richman, a singer and guitarist from Boston, who at the time was leader of The Modern Lovers. A mix of child-like naivety and raw energy, his songs had the same joyous vitality that leaps out of Combas’ canvases.

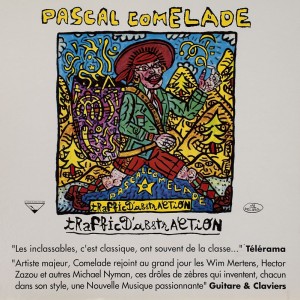

Les Démodés, the musical trio that Combas formed with Ketty and Buddy, brother of Hervé Di Rosa, was meant to be a trash version of The Modern Lovers’ exalted candour. They were a cult group, but they split after only fifteen gigs. Still, Combas never entirely gave up on his desire to compose music. Where previously the two worlds had seemed to ignore each other, the 1980s saw a rash of rock and visual arts crossovers. Robert Combas worked on occasions with groups like Taxi Girl and with artist Pascal Comelade, but he regretted that the connections were less frequent than in the UK or US.

His appetite for records grew even more in the New Wave years, when myriad groups (Devo, Talking Heads, XTC, Joy Division, Pere Ubu), liberated by the punk ethos, ventured further into bold experiment, producing a prodigious variety of styles. In the 1980s the roughest rock could join up with funk and synthetic pop, and, inspired by musical thinkers like Brian Eno, open up to ethnic music and its more contemporary mutations.

When penniless in Sète, Combas often used to nick his vinyls. In Paris, he bought albums and singles like there was no tomorrow, building up an extraordinary collection driven by his passion for music, but also his attraction to record covers and the unusual.

Ever since then, his curiosity has explored the most out-of-the-way veins of pop, going freely back in time, crossing stylistic and geographical borders, to the point where, overflowing with inner rhythms and melodies, he plugged his instruments back in and started reinventing musical paintings. As a result of which he could say, “My rock is painting.”

Stéphane Davet

![[EN] Combas.com](https://www.combas.com/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/01/logo-reseau.png)