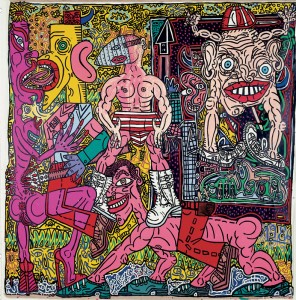

Let’s Roll.2 For going on four decades, Robert Combas has painted, and painted frenetically, without ever lowering his guard or slowing his rhythm. He paints on the wall and onto the wall, on the floor most of the time, and all the time. Generally, when he talks, his back is bent as he traces, dips and sometimes scrapes. He stamps, stops, goes off at a tangent and returns, changes colour and side, then whispers his line and, as if by a miracle—but naturally – the image comes. Urgently. He throws himself at his canvas like Kurt Cobain3 grabbing at the neck of his axe, but Combas caresses his canvas and the colour spreads out and comes towards us.

Robert Combas is a fabulous storyteller. What he says he always says twice: first, in an image, and then in words. For each painting is accompanied by words, but these words do not ape or comment on the image, any more than the image illustrates the sentence. And it is in the floating space between these two visual forms, “seeing” and “reading,” that Combas compels and catches us. He traces out the full extent of our imagination: our mental image. He sets the path of our interpretations, all the way to the infinite digressions that he gives us and whose secret is his. Combas paints for us, not for Great Men, not for History, not to make yet one more image, even less to formulate a theory. He paints what happens. “Reality is what happens,” said the philosopher.4 What happens to us! We all have “a battle between cowboys and Indians” in the back of our mind (today, that would be GTA or Modern Warfare),5 a Trojan War that never happened,6 or a “Ketty” we were mad about.

What happens. This is probably the secret of Combas’ dazzling success on the cusp of the Punk Years, at the very end of the ’70s, last century. Never Mind The Bollocks.7 His cry in those years probably emerged from the art of silence in which he had confined himself and from his tranquil aspirations to eternity. But what happens is soon gone! That is also, probably, the reason for Combas’ relative wilderness years. Time was strangely out of joint: after the love and enthusiasm of (art) critics, now came indifference, then withdrawal, and then finally forgetting. People moved on to something else. But the public kept faith.

This was a curious situation that, retrospectively, makes Combas less an artist than a symptom. For critics, indeed, and more generally for the artistic institution, he was something like a perfectly prepared prey for sociologists hunting for academicism. He was described, in effect, as a societal phenomenon. He began as the leader of the “Figuration Libre” pack (the name, coined by Ben, was apt), which limited his work to a given “generation”.8 Then he was presented as a standard-bearer, that of a people who were subaltern but miraculously saved from anonymity and mediocrity by his loquaciousness, accommodated for a while by Great Art, like Boudu, still wet before he was finally drowned by precisely the same people who rescued him from the waters. Here the image of social origin (and when this is stressed, it is because it is exotic, that is to say, more low than high), acts as a screen, as if it explained everything else, like an essence, as if Robert Combas had not constructed his own identity, as all important artists do. Then the artist became a caricature, like the one they turned Fernand Léger into (he too was a painter of colours and outlines) —a solid, thick bumpkin (a prole, but of peasant origin). The comparison with Léger goes no further, but we can at least note that he was the first person to express the immense creativity of the people-as-poet, whose slang he discovered in the trenches (in 1914). Then Combas appeared as an heir—not the privileged caricature found in Bourdieu, but as the worthy successor of Dubuffet: as if art, like cider, a boxer or cement, must by definition be raw and unrefined if it is direct and deliberately so. And Combas’ art brut did not exist? Fine, he was turned into a semi-Picasso. He had his persistence, without the ease. In short, Combas was never Combas. But what he said about himself was above all that he was not learned. And that’s something you can’t get away with.

And yet, Combas’ erudition is undeniable: it is the erudition of every possible image. Every available image, and all the others too. And if, when he talks, Robert digresses, that is precisely because he talks in images, which is also how he paints: in images. In this sense, he clearly anticipated the computer generation, the generation of screens, information flows, an unceasing bombardment of images that have no origin or history, and that are often cobbled together. Robert Combas has always maximised the plasticity of the image, asserting the idea—a simple idea yet so difficult to get—that there is no purity, and therefore there can be no hybrids; that there are only processes, only stories and narrative. There are only transient states of which, at each moment of our own lives, in each lived second, we are the most convincing illustration. All his work tells us that we are a product of our own making, for there are no autochthons either, no fixed identities or determinisms, just the plasticity of which we are at once the products and the actors. History, our history, is merely an endless process of recomposing and borrowing, of slow mutations or radical collages and disruption. There is no pure image or pure being, only alchemy, attraction or rejection. For Combas, there is no master narrative, no definitive, complete work, but only modest attempts. Attempts, though, that are made every second. Each time, we replay what we are, and that is how, little by little, we become different: all the same, but all different. No great narrative, but small, precise, incisive and infiltrated stories, like popular songs, the Proustian Madeleine for ordinary people. The kind that bores into our imagination, infuses our memory, sometimes make us nostalgic, and makes us what we are, we who resonate more intensely with the sounds within us. The proliferation of images is now the domain of the netizen, the patois of the painter, you might say. Robert Combas knows that the netizen is the artist’s great rival, and that he is often at least equivalent to him in terms of invention. But unlike the netizen, the painter stops the image and turns it into something more substantial. The resulting image has a scale and a color—pink, say— that some are quick to take up. And the art of painting, from the cave paintings onwards, has always been to give life, dimension and presence to an image and make it something unique, that is to say, an artwork. And Combas keeps his work within the realms of seeing. To say seeing is not simple but, as the philosopher said, “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.” Thus, to say seeing is not to write it but to show it. And that is what Combas does. This is where we can at last, without words, speak of painting. This is how a given colour, a given “scribble” or line—like a line of thought— speaks the world. Speaking the world: “This is how I came to realise that all the things one loves become beautiful in art. Beauty is none other than an expression for something that has been loved.” These words were written not by Combas but by Robert Musil.9 Two worlds that could hardly be further apart, and yet: “As a young person, one day you find yourself in a strange land of which only the immediate surroundings are familiar. There are people with you who point out the paths to be taken next and then leave. In this land, which is both alluring and frightening, you now cautiously begin to move toward what attracts you, and to face up to what scares you. This is how you start to build a relationship to the world, one that is both outgoing and interiorised. I think that most people go through this process, and for most creative writers and artists, it’s their point of departure. […] It was different for me. I began aggressively and found my bearings by forcing the image of the world into the highly imperfect frame of my ideas. I only mean, of course, that I did this a bit more than other people. The desire to be a law unto oneself is distinct from the desire to find a good position in life and different from the amazed question: ‘How did I come to be here at all?’—the notion might be expressed in roughly these terms.”10 Combas asks the same questions as the author of The Man without Qualities, who is quoted fairly extensively here, but with the added text in italics.

The world… What happens… Ever since he started painting, Combas has never ceased to tell us that we have no other time but our own, and that it is urgent that we make the most of it. That is why he wrote: “My painting is rock music.” His canvas is the stage, the magic square where at last we are on our own, facing the world, at the Voodoo crossroads where the blues digs in and hides, the unplugged blues of the cotton fields, and the electric blues of Burning Motor City.11 Never mind where it is. Burning Your House Down!12

Fragile Beauty: “My painting is rock music.” Combas plays it with six strings and clapped-out drums all blown apart and the body thrust forward, at breaking point.

Dazzling beauty. Born to be Wild.13 La Fille du Père Noël,14 the same riff as Hoochie Coochie Man.15

And above all, I love you tender.16 Tenderly.

Tragic Beauty: Maybe all he’ll leave behind is an infinite mass of glimpsed fragments, of suffering shattered against the world, of years lived in a minute, of unfinished and frozen constructions, of huge undertakings seen in a glimpse, and dead. But there is something rose-like about all these ruins. These last two sentences are well suited to Robert Combas. They are by Paul Valéry,17 as if the somewhat anarchist poet and Academician were to meet up with Jim Morrison, fallen angel and leader of The Doors, over a glass in the last whiskey bar, to words by Brecht.18

All this is what makes Combas Combas: intensity, tragedy, humour, and life

—above all life!

And Art? Combas confronts it mano a mano. The face? He has hammered it. The portrait? He has sung it just like the battles, just like the monsters, and like ourselves, and the ghosts of the night, and the bad side of the road19… Mystery Dance,20 and Dachau Blues21 …

His art should be seen the way we listen to rock music. It is rock. That is what I said to Robert Combas when I called him to suggest this retrospective. Robert said, “That’s funny, I’m doing rock at the moment, I’m one of the Sans Pattes with Lucas Mancione and Geneviève: I have fifteen pieces post-produced, an album in mind, and I’m still a painter.

That is why the exhibition is called Greatest Hits, like his painting from 1986.

And because there’s no stage without a backstage, and no painting or sound without a studio, I suggested that Robert should move into the exhibition for two months. Live. In a studio that is visible and visitable. With no miming. There will be four concerts, with a stage for Combas Rock. And above all, four decades of painting and music, to be seen in the galleries and on the playlist.

My brother he starts raging!

Watch him rising see him howling!22

But most of all: Gimme Some Lovin’.23 Love.

Over 650 works, from the ballpoint doodles on young Robert’s school exercise books, that show his encyclopedic range and insatiable thirst for images, all the way to the Major Paintings; and sound, everywhere. Just life, in colour.

Hey! Save the Last Dance for Me24

Enjoy the show.

Thierry Raspail

- Pierre Michon, L’Empereur d’Occident, Paris: Verdier, 2007, p.28.

- Let’s Roll is a song on the Neil Young album Are You Passionate? (2001).

- Kurt Cobain, guitarist and singer of the Seattle trio Nirvana, entered rock legend with Nevermind, 1991, a monument to grunge and allusion to the Sex Pistols.

- Marcel Conche, L’Aléatoire, Éditions de Mégare, 1990.

- Video games, GTA: Grand Theft Auto, Modern Warfare: MW, car games.

- A reference to Jean Giraudoux’s book La Guerre de Troie n’aura pas lieu.

- Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols is the only original album released by the Sex Pistols. It came out in 1977 in the United Kingdom.

- The Leader of the Pack by Spector, Barry, Greenwich, 1964. The French version, Le chef de la bande, was sung by Mino.

- Robert Musil, Diaries 1899–1941, Basic Books, 2000, p. 353.

- Ibid. p. 452.

- Song by MC5 on Kick out the Jams, recorded live at Russ Gibb’s Grande Ballroom,Detroit, October 1968.

- Burning Your House Down, an album by The Jim Jones Revue, 2010.

- Born to be Wild was written by Mars Bonfire in 1968 and brought fame to Steppenwolf and its singer John Kay.

- Jacques Dutronc is the self-titled first album by Jacques Dutronc, released 1966. It featured his first hits: Les play-boys, Les cactus, Et moi, et moi, et moi, On nous cache tous, on nous dit rien, La Fille du Père Noel et Mini-mini-mini.

- Muddy Waters – Hoochie Coochie Man, 1954

- Reference to Love Me Tender by Elvis Presley,1956, and I Wanna Love You Tender by Danny & Armi, 1978.

- Paul Valéry, Cahiers, 1894-1914.

- Jim Morrison, lead singer and songwriter of The Doors. Their first album featured Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar), words and music by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill.

- Reference to Walk on the Wild Side, a song by Lou Reed on his 1972 album Transformer, produced by David Bowie.

- Mystery Dance, lyrics by Elvis Costello.

- Dachau Blues by Captain Beefheart on his 1969 album Trout Mask Replica.

- Mickey Mouse And The Goodbye Man, from Grinderman 2, 2010. Grinderman is the group formed in 2006 by Nick Cave with Warren Ellis, Martyn P. Casey and Jim Sclavunos, all of whom played in Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Their first album came out in 2007.

- Gimme Some Lovin’, Spencer Davis Group, 1966.

- The Drifters, 1960. When Doc Pomus wrote this piece he was in a wheelchair with polio. He dedicated the lyrics to his future wife: “You can dance […] Go and carry on […] darlin’, save the last dance for me.” See the fantastic version by the Troggs on The Troggs on 45’s (1982).

![[EN] Combas.com](https://www.combas.com/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/01/logo-reseau.png)