If Robert Combas can be said to have an artistic ancestor, then it is the anonymous artist who drew and painted the odysseys in prehistoric caves by the yellow light of torches, amidst the feral perfume of lamps burning animal fat. You only need to see him turn away from his easel and, ecce homo, it’s easy to picture him, his hair just a little more tousled, his clothes replaced by animal hides, bearded, dirty and hirsute, looking perfectly at home among a primal horde of the Magdalenian era. Combas is a shaman: he paints like a shaman, he thinks like a shaman, and he lives like a shaman.

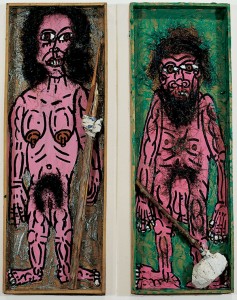

La Tribu préhistorique (The Prehistoric Tribe, 1999), a series of works made for an exhibition in a region known for its prehistoric art, bears witness to the fact that for him this Palaeolithic Way of the Cross operates like a family tree: in these vertical portraits, Combas mixes hair and paint, stone axe and stick, string and bow, sling and contemporary hairbrush, to produce a series of icons of a paganism that goes back several millennia, in which woman and man appear in all their natural majesty: hirsute, with flaccid genitals and sagging breasts; warriors, open-mouthed with bared teeth, they propose a genealogy of the world, and therefore of the painter, and therefore of painting.

La Tribu préhistorique (The Prehistoric Tribe, 1999), a series of works made for an exhibition in a region known for its prehistoric art, bears witness to the fact that for him this Palaeolithic Way of the Cross operates like a family tree: in these vertical portraits, Combas mixes hair and paint, stone axe and stick, string and bow, sling and contemporary hairbrush, to produce a series of icons of a paganism that goes back several millennia, in which woman and man appear in all their natural majesty: hirsute, with flaccid genitals and sagging breasts; warriors, open-mouthed with bared teeth, they propose a genealogy of the world, and therefore of the painter, and therefore of painting.

In the same way as the anonymous artists at Lascaux, Cosquer and Chauvet painted the vibrations of the cosmos, Combas is driven by a similar tropism. What do we find in the caves of Homo sapiens sapiens? Sex and blood, in other words, life and death. Nothing more. Vulvas? Callypigian Venuses? Wide hips? Heavy breasts? Copulation, sometimes even with animals? Sex. Assegais? A man falling flat on his back? Hunting scenes? War? Fish hooks? Death. There’s no getting away from it. Negative or positive hands? Probably a sign of appropriation, and therefore of sex and death at the same time. Paintings by Combas are packed with vulvas, callipygian Venuses, wide hips,heavy breasts, copulation, assegais, wars, hunts, including modern ones —individual terrorism, bombs on a bus or state terrorism, the war in Iraq.

A seismographer of the cosmos, Combas reproduces the likely prehistoric configuration in which the artist, priest, wise man and philosopher were one and the same person. Little is known about the prehistoric cave painters, or how they saw the world, or how they interpreted the cosmos, although we are sure that they knew infinitely more about the sky, in the broad sense of the word, than most of our postmodern intellectuals. This gap in our knowledge about the minds of our ancestors has often been filled by the speculations of pre-historians. The priest known as Abbé Breuil, the lustful but tormented Georges Bataille and the structuralist mystifier Leroi-Gourhan all imposed their autobiographically oriented interpretations on what they saw, rather than acting as shamans of what was produced by a force that Bergson called the élan vital.

Just think: people who were tens of thousands of kilometres apart, and with no means of communication or travel, who were not even aware that their fellow humans existed—these people were painting the same thing in the same way at the same time! It was impossible for them to copy or plagiarise each other, or take inspiration from others, as is so often the case in the modern world where networks of all sorts—road, rail, air, postal, digital, telephone— connect people across the greatest distances. There was, it would seem, a time when the artist reproduced the world-psyche, when he or she expressed the quintessence of the cosmos. Robert Combas may be a contemporary of the computer and mobile phone, of supersonic flight and moon landings, but he marvellously embodies the Rimbaud-like preaching of the visionary artist.

In the past, as in the present, and probably in the future, the visionary artist drew directly on the energy of the world. This is clearly evident in Combas’s style, which

celebrates colour as if it were a force, and in his use of line, which seems to enclose magnetic fields. As we have known at least since Goethe and Schopenhauer, and more recently from physicists, colour is a vibration; it is therefore energy. In the panorama of contemporary art, Combas is one of the very few who makes these energies dance. Not vibrate, or wiggle, or shake or quiver, but dance. And we know that dance means trance, and that trance leads to the doors of what must be seen.

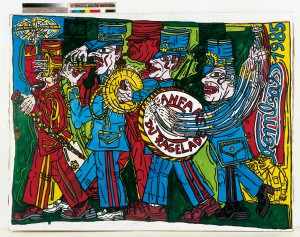

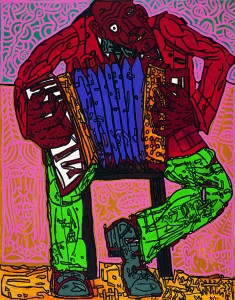

Combas is a shaman, too, through music. His painting is noisy. Chromatically, of course, but also by virtue of what it makes us hear: a bass drum, cymbals, a whistle, a trumpet, or the eight violinists of an octet named L’orchestre de quelque chose (1999); or the accordion of Accordéon Gérardinosto (2008); the banjo in La fanfare du Ragelade (1985); a symphony orchestra here, a flute there, not to mention the configuration that is most emblematic of the man: the rock group, as in Le Velvet Underground (1990).

Combas is a shaman, too, through music. His painting is noisy. Chromatically, of course, but also by virtue of what it makes us hear: a bass drum, cymbals, a whistle, a trumpet, or the eight violinists of an octet named L’orchestre de quelque chose (1999); or the accordion of Accordéon Gérardinosto (2008); the banjo in La fanfare du Ragelade (1985); a symphony orchestra here, a flute there, not to mention the configuration that is most emblematic of the man: the rock group, as in Le Velvet Underground (1990).

In every shamanic ceremony there is a ritual in which music plays a major role. As we have seen, Combas already has the body of a shaman. Those privy to this world’s secrets say that a particular kind of body is called for, a body at once fragile and strong, atypical, with special capacities that make it out of the ordinary. It must have a tendency towards hyper sensitivity, a talent for synaesthesia, in other words, a consummate gift for seeing music, smelling an image, transforming colour into sound, hearing images—for using the senses to approach objects in an unusual way: the eye with sound, the ear with images, the nose with melodies, the mouth with chromatic vibrations. Combas excels in this art of mixing up the senses to achieve illuminations that lead into the clearing of artworks. He has the right kind of body.

The shaman uses his body like an instrument. He subjects it to a kind of ontological tapping to extract the sap, the quintessence. The preparation implies fasting. A purification of the flesh that puts the organism in a state of tension: no solid food, no liquid, a moment of organic voiding. The electricity builds up, his breathing changes, as does the circulation of the blood; the heartbeats change; sight and hearing slowly but surely metamorphose. He sees differently, smells differently, tastes differently. The tongue says a note, the nose sees a colour, the eye smells a perfume, the ear hears an image. This body is ready to receive extra energy. All shamanism involves the consumption of hallucinogenic substances or drinks. In Arctic civilisations these consist of lichens, mushrooms and mosses; in the Westernised world, alcohol, soft or hard drugs with soft and hard uses of soft drugs or soft and hard uses of hard drugs. Robert Combas has made no secret of having taken some of these vehicles that are sacred beyond the polar circle or in tribal worlds, illicit in our lands. Hashish, wine, opium, mescaline, heroin and LSD have long been companions of the true greats—Baudelaire and Kerouac, Burroughs and Michaux, Jim Morrison and Sartre, de Quincey and Wilde, Warhol and Basquiat, to name but a few.

The shaman uses his body like an instrument. He subjects it to a kind of ontological tapping to extract the sap, the quintessence. The preparation implies fasting. A purification of the flesh that puts the organism in a state of tension: no solid food, no liquid, a moment of organic voiding. The electricity builds up, his breathing changes, as does the circulation of the blood; the heartbeats change; sight and hearing slowly but surely metamorphose. He sees differently, smells differently, tastes differently. The tongue says a note, the nose sees a colour, the eye smells a perfume, the ear hears an image. This body is ready to receive extra energy. All shamanism involves the consumption of hallucinogenic substances or drinks. In Arctic civilisations these consist of lichens, mushrooms and mosses; in the Westernised world, alcohol, soft or hard drugs with soft and hard uses of soft drugs or soft and hard uses of hard drugs. Robert Combas has made no secret of having taken some of these vehicles that are sacred beyond the polar circle or in tribal worlds, illicit in our lands. Hashish, wine, opium, mescaline, heroin and LSD have long been companions of the true greats—Baudelaire and Kerouac, Burroughs and Michaux, Jim Morrison and Sartre, de Quincey and Wilde, Warhol and Basquiat, to name but a few.

A visionary’s body, fasting, and hallucinogenic substances, the time is set by music. The shaman prepares to enter immanence, where he will find transcendence. Most of the time, percussions strike up a paean to the cosmos. The skins of dead animals have been tanned then stretched over the frames of percussion instruments.

A bone serves as a drumstick. On this animal vellum the skeleton writes a melody. The rhythm and cadence build up series of repetitions. The body follows the folds of these melodic lines, and the continuous folding sends it into a trance.

Combas experiences these trances with his rock group. First with Les Démodés, and then new group, Les Sans Pattes. In his comments, Combas writes: “My painting is rock music, the search for feeling. The feeling is the rhythm, the wild drummer in the jungle and voodoo dances. It’s The Rolling Stones copying old pieces by Blacks and Bluesmen, and creating a new music without even meaning to.” Rock, feeling, rhythm, wild drummer, jungle, voodoo dance: safe to say, we are very much in the shamanic register.

These concerts are a chance to hear Combas’s singing voice. In a singular way, it does not seem to match his body. His speaking voice is not as deep as his singing voice. It is as if, caught up in the electrical folds of the music, enveloped in the rhythms and cadences, the vibrations of his larynx, like those of his painting, are more chthonian—in other words, more in phase with the earth, caves, the ground and the underworld. This chromatic and aural spectrum defines the substance of his voice, which becomes the mediator of the breathing of everything that lives.

Shamanic music is repetitive, as is Combas’s: built from minimal cells. It makes you think of that American contemporary music which allows for variations on difference and repetition through the repetition of a single cell that varies infinitesimally with each occurrence, so that over time it shifts towards another form. In it we hear the metamorphosis prized by the shamanic psyche, which conceives of man as an animal, of an animal as a plant, a plant as a mineral, a stone as a cloud.

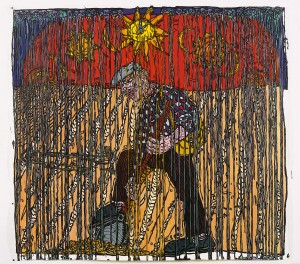

There is one big canvas that seems emblematic of Combas the shaman’s presence in this world: L’Autiste dans la forêt de fleurs (1991) (Autistic in the Forest of Flowers).

Here is the long text that constitutes its full title: “The sad fool loves life, but he is autistic and able to converse only with his forest of flowers of which he is the king.

His subjects honour him and decorate him with their multicoloured petals, and their illuminated perfumes fire cannonballs from the luxuriant smell. The sad fool is in paradise, but he is autistic. When will he regain the life that is gradually slipping away? He knows he is on the right path. Already, the lunar earth has disappeared and given way to all the flowers of mental creation. How much longer must he wait without being able to talk, sing or laugh? He has already erased winter and autumn from the cerebral calendar.” That’s it.

Why is it emblematic? Because of the autism? No. We are all autistic to some extent, it’s a matter of degree not of nature. Artists, designers, philosophers, writers and composers tend to spend more time in their inner world than in the world of others. Is that what we should call autism? And for the sad fool? No more so. The fool is not lacking in reason; rather, he uses another reason. Combas resorts to it in Dionysian fashion: he uses spermatic reason, Bacchic reason, libidinal reason, shamanic reason of course, impure reason, chromatic reason, synaesthetic reason, musical reason. And what about the sad part? Perhaps, but sadness is a grey passion and Combas never paints in grey.

This long canvas (216 x 518 cm) shows a man who is like a flower in a forest of flowers. We know that petals, pistils, sepals and stamens are different parts of the same thing: a sex. Who, when gazing deep into the corolla and calyx of an orchid, for example, has never thought of the mysterious entry of the opening of a woman and of the promises of travel it conjures up? The primal Garden of Eden from which this sad fool’s head emerges is an orgy of women’s sexes. Exploding colours, luxuriant smells, illuminated perfumes—the canvas is made to be smelt and heard as much as it is to be seen. The artist is not so much autistic, more a magic flower obeying the injunctions of the cosmos. The shaman becomes tiger and flower, snake and rock, mist and wind, silence and colour—here, Combas blooms as a flower among flowers, like a heady simulacrum, a shower of atoms or a flight of particles wafting through the air the way a note of music crosses spaces, breaking off from the music of the spheres.

The shaman is like a flower in a field of flowers. Or like a star in a cosmos. Or a wolf in a pack, a bee in a hive. For he dons every possible garment of the real. Like an artist. Like Combas. In this way our artist can play the sad fool, the perfumed autist, the subject of a king of petals, the brainless wonder of the cerebral calendar, the exile from a lunar land, a voiceless singer, a closed-mouthed laugher, mutely awaiting nothing, for the noise of the cosmos echoes through him – it is the voice that he uses on stage.

For Robert Combas, then, trance is knowledge, or at least, a means of access leading to knowledge. His world of colours and drawings, of forms and forces, finds pretexts in a multitude of themes. Hence the colliding objects in the sculptures—a signature on legs, guitars decorated with Van Gogh motifs, a horse on wheels mounted by a weirdo coiffed with a broken Eiffel Tower, a galleon worn as headdress by a naked woman, a long armchair scratch-marked with colours and smooth metal.

This genius for collision culminates in a series of crucifixes constituting the Pagan Passion of Everypainter: old brushes, tubes emptied and crushed, having yielded all their liquid the way others bleed their soul, are all given ironic, whimsical and sarcastic new life in an assemblage two millennia old: a Christ on the Cross. A cross of brushes, Christ’s body as a tube: hang the latter on the former and you have a new story, about the painter who suffered and died to save humanity!

Combas also fits some pagan figures into this zoo of characters created with the painter’s junk, his bins, his crumbs, his leftovers: the brush bristles are the hair, its reservoir is the head, its ferrule the neck, the handle its body, adding up to a character ready to live its life. Sometimes, two handles stuck in a ferrule simulate the upper limbs—the brush is opening its arms. Elsewhere, a strange crew speaks of a kind of dinosaur with a humanoid on its back. So, there is plenty for the Crucified to do in this world which may come alive the moment the viewer devoid of imagination has turned his back on it. The shaman is not autistic. He is a creator of alternative worlds.

As well as these collisions and objects that conjure up parallel worlds, Combas sometimes broaches themes that are baroque in their eclecticism: versions of famous paintings in the Louvre; envisaging—quite literally, putting a face on —the Siege of Troy; representing great battles; revisiting the portraits of Christian saints; paying homage to Toulouse-Lautrec; celebrating Georges Brassens, another of Sète’s native sons; magnifying the world of flowers, pictorial variations on the legend of Scarbo by Maurice Ravel; dressing clothes in paint; working on photographs in counterpoint of their colour; going head-to-head with the theme of the vanitas; juggling with skulls and skeletons; setting up a mirror between the fall of man and the fall of the angels, etc.

Each of these periods warrants lengthy discussion, and could form a chapter in its own right. I have chosen Pauvre Martin (d’après la chanson de Georges Brassens) (1992), firstly, because this canvas reminds me of something the artist said: “I come from a family of six children. My father was a labourer and my mother was a cleaner.”

That’s it. But note that Combas is not an heir, in the sense Pierre Bourdieu attaches to that word—namely, one of those individuals born with a cultural silver spoon in their mouth—but someone who had to learn the codes for himself, which gives real freedom with regard to bourgeois cultural dogma. The working slower off the mark, but he goes further than the heir, who is hampered by having it

so easy. The Nietzschean version of what does not kill me makes me stronger is also illustrated in the artistic path of someone not born to such a profession. It also happens that Pauvre Martin embodies the agricultural version of the proletarian world —and that my father was an agricultural labourer. Second reason. I share with Robert Combas this fidelity to a world in which culture has no right of abode.

What is Brassens’ song about? The story of an agricultural labourer who sings as he works, who really puts his back into his work, his nose to the grindstone, who earns his crust by ploughing other men’s fields, who never complains, is never jealous, never wrongs others, and who, the day death invites him to plough his last field, digs his own tomb and lies quietly down so as not to bother anyone, then enters the ditch opened in the glebe that he has dug all his life. The Virgilian life of a labourer lived by millions of others like him, from prehistoric times until the arrival of the internal combustion engine.

Robert Combas paints this meditation on Virgilian time. In a blood-red sky, the sun marks its course; at the heart of the star itself a clock tells the time. The sun rising, at its zenith, and setting: the painter speaks of a man’s birth, childhood, youth, maturity, old age and death, within the universal scheme of things. This inevitable existential trajectory is written into the cosmos: the painter’s sky also seems to be a kind of star, like another sun in which suns might follow paths ordered like clockwork. The clock says one and, just as we say once upon a time, here we could say, it was one o’clock —that one terrible hour, after which there will be no more time.

This is the hour of death foretold: the figure of the future corpse is already lying on the earth. Soon, it will sink into it like black rain. The simulacrum of a corpse—the simulacrum according to Epicurus is an assemblage of subtle atoms that have left the thing itself but retain its form and move through the air, reaching the eye of the beholder—seems already stiff, laid out, arms by its sides, disembodied: in other words, already without flesh, a material soul, psyche of earth on clay, an empty envelope bereft of the breath stolen by the final hour. The ground has been tilled, the furrows lead to the cosmos—unless it’s the other way round and they are going from the cosmos to the ploughman: the cosmos holds the destiny of each one of us: Martin’s and everyone else’s.

In the foreground, in front of the glowing cosmos, standing out on the brown earth combed by the ploughman’s toil, the agricultural labourer, stocky, strong and powerful, “digs the earth, digs time”, says the song. Cap, checked shirt, corduroy trousers, boots, lunch bag for food and drink: the man is emblematic, ancient, cosmological, ontological, and metaphysical. He is the labourer of the earth. There is no watch on the wrist of these strong, hairy arms. His big hands are on the shovel, his foot pressing its blade to make it break the ground, the ground that will receive the body of this man who will die.

Taciturn, silent, following the cycles of nature, wise without affectation, Virgilian, although he has never even heard the name of the poet who wrote the Georgics, “Martin”, like the shaman, was not separate from nature. The agricultural labourer, too, is a shaman, like Combas, a worker of time. Coming from the earth, he returns to the earth having worked the earth. His own sexton, he digs his grave without troubling others because he has long known that he lives in the fields where his destiny lies. In the foreground of this work, a curtain of paint, drips—just as sweat drips down the face of poor Martin. The shaman Combas paints a lot of blood and sperm; here, he paints sweat, another secretion, another seminal liquid, another ontological substance.

In this way, deceptively, Combas paints deep existential truths. Where the champions of so-called legitimate culture base their work on purportedly noble references, this artist from a working-class background draws on the simple, modest repertoire of popular song. Institutional and official artists quote Joyce or Jabès, Webern or Boulez, Mallarmé or Celan. As the son of a labourer, Robert Combas, the prehistoric painter, inspired shaman, Dionysian artist, and psychedelic rocker, draws on a song by a strummer whose tunes are whistled by all and sundry—indeed, the “sweet song” on poor Martin’s lips could easily have been a Brassens melody.

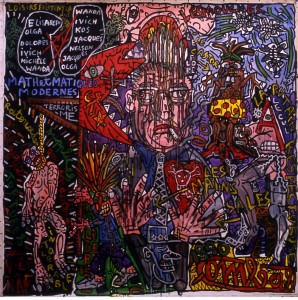

There is another canvas in my personal museum: Jean-Paul Sartre. Its date, 1990, marks the beginning of my interest in Combas’s painting. I happened to be sitting in front of my television, one night in 1990, for a programme about the philosopher. Given the year, it was probably a slightly early commemoration ten years after his death. There was a learned assembly of Sartrians. I recorded this High Mass on videocassettes. They are probably in my attic. I remember a café, presumably one of Sartre’s two HQs in Saint-Germain-des-Près, and this live performance by Robert Combas: painting this portrait!

It was, of course, a great shamanic exercise. The text accompanying the title is worth quoting in full: “Greatest hits: Jean Paul SARTRE plus Simone as guest of honour. Nausea because he’s being puked upon, Le Castor alias Simone, Modern

Mathematics with lovers and mistresses with Simone (encore), Dirty Hands and

Charles. Algeria with torture, Arab-bashing, violence, in short, pure intolerance, plus a biting Communist flag, flies and the respectful prostitute (which doesn’t mean she doesn’t give head). But that’s only my opinion.” This square canvas (158 x 158 cm) gathers up a philosopher’s life the way Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights is a kind of Adamic dream.

A Prévert-style inventory: a Sartre with glasses and squint, thick lips, fag in mouth, fatty, flaccid, warty face; a man, mouth wide open, is throwing up over him. Nausea effect; a kind of red dragon, a hammer and sickle striking its jaws, but also by a fivepointed star, symbol of imperialism on every continent, opens wide to swallow the philosopher—nice touch; a purple shirt with a tie that looks like the Eiffel Tower; the bit of fabric hangs down from his neck to his navel where General de Gaulle in three-star kepi is raising his arms in a “V” for victory, or the Fifth Republic; Sartre’s heart, blood-red, contains a death’s head—another nice touch.

Simone de Beauvoir appears on the right of the canvas—she was called

“Le Castor” because that animal’s name in English is “beaver” and, as her Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter tell us, “Beavers like company and they have a constructive bent”—with the words “Le Castor” painted in yellow and an arrow painting to the author of the Second Sex. She is wearing a turban from which her hair is spilling out like a tropical plant. She has two beaver-like teeth, the animal’s nose, its quasi-nudity, except for a very un-sexy pair of canary-yellow pants with big red dots, with bare legs, and she is wearing red high-heeled shoes.

A series of words constellates the canvas. Apart from “Le Castor” and “Simone,” the nickname and name of the woman of “necessary” love, the names of a few contingent loves, in other words, the mistresses that Sartre demanded the right to collect when he imposed a pact that, for the sake of the legend, Beauvoir later presented as a mutual agreement. “Jean-Paul,” a Sartrian bubble, as the accompanying portrait attests, encloses the names of “Elisabeth,” “Dolorès,” “Ivich,” “Michèle,” “Wanda,” and opposite it another, Beauvoirian bubble, “Simone,” (with another portrait, just as unflattering, in green lines, showing only the head, as weird as ever, a cross between Josephine Baker and the Banania label), contains the monikers of “Wanda,” “Ivich,”“Kos,” “Jacques,” “Nelson,” “Jacques,” “Olga.” Red arrows connect up some of these names. Above this diagram we read “existential leisure”; below, “Modern Mathe – matics”—the fact was that this sexual and libidinal mathematics was all about dark calculations. Other words signal the legendary Sartrian meeting place, Le Flore café, and the titles of books. Dirty Hands (Les Main sales) refers to the hands of De Gaulle, The Respectful Prostitute (La Putain respectueuse) accompanies a woman’s body with stockings, garter belt, high heels, bare buttocks and breasts: “the ass,” “The Flies” (Les Mouches) is adorned with three big insects and the green trails they leave in space.

At the bottom, on the left, Sartre is naked and hanging from a gibbet. The words accompanying this sequence on the canvas: “Terrorism,” “Ratonade [Arab hunt] in Algeria,” “Torture in Indochina,” “Torture in Vietnam,” “intolerable.” This political sacrifice makes the philosopher a victim of the populace, who hounded Sartre who championed the colonial independence struggles. Between the political Sartre and De Gaulle, between the Leftist philosopher and the right-wing president of the Republic, an angry student wearing a kind of smock with the words “Faculty of something” holds the gibbet from which Sartre hangs. Between the student and the philosopher is the word “Freedom.”

So much for a quick phenomenology of the canvas. What does it say? It sums up the philosopher’s life and work, his battles, his writings, his political commitment, the places he frequented, his women, his love life and sex life, his adversaries, his enemies, his causes, his counterpart at the Elysée. Everything is said in a jumble, but contained in the same space, as if in the same life. We find the raw material of what Sartre called an existential psychoanalysis: a philosopher threatened and devoured by Communism, a fighter from the Algerian War waged by General de Gaulle, a flesh and blood creature living a life with a “pivotal companion”, to use Fourier’s vocabulary, and butterfly women, considerable public hatred, the work of a writer and dramatist generating flies, whores and dirty hands to the first degree, all in an extended shambles, a baroque load of clutter, a saturation of information that sums up nicely what a life is like.

Whether it be an agricultural labourer or a legendary philosopher, indeed for any subject, Robert Combas proceeds in the same way and grasps the substance of beings as he does of the world or the cosmos: by the handful, kneading and pummelling and massaging, manhandling the paint like a potential force, vitality, a powerful energy that it is his job to activate. He is directly connected to that force, plugging into the electricity of the universe. His unique style is that of a primitive genius who sculpts time and piles up works as testimony to the freezing in time of these magnificent durations.

This shaman is the great organiser of chromatic festivities, the officiator of a pantheistic religion whose devotees are those who are magnificently alive. Long live the shaman!

A shaman called Combas – Michel Onfray

![[EN] Combas.com](https://www.combas.com/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/01/logo-reseau.png)